Click on the icons on the map to reveal some of its

characteristics.

Information

Source

Image

Painting or Map

This canvas from 1614 belongs to two different genres:

landscape painting and map. Although it was made to serve as

evidence in a legal trial over land ownership, the

manuscript is not a simple outline, as used to be the case

with maps at the time. Instead, it delves into the artistic

terrain with its singular use of color, its elaborate

designs and the inclusion of the signature of the author,

Juan de Aguilar Rendón. These three elements tell us that

the author was interested not only in showing the

distribution and use of land for the trial, but also in

creating a piece that could be appreciated for its aesthetic

qualities.

Dispute over Lands

In 1603, Francisco Maldonado y Mendoza was accused of having

defrauded the monarchy by buying large and fertile terrains

at a very low price, and was taken to court. The purpose of

the painting was to illustrate the land to allow the court

to judge if the accusation was true or if Maldonado was

right in claiming that the land was nothing more than a

barren wasteland. Annotations such as “useless marsh” or

“swamp land” were fundamental to the development of the

trial. The court ruled in favor of Maldonado and ratified

his rights over these terrains.

The Village of Bogotá

Although Colombia’s capital was known for a long time as

Santafé de Bogotá, on the painting we find two different

places: the “village of Bogotá” (today the town of Funza)

and the “city of Santa Fe” (today Santafé de Bogotá). This

is due to the fact that the creation of villages was a

policy designed to instate two different republics,

spatially distinct and with different legal

responsibilities: one republic for Indians living in

villages and one for Spaniards living in cities. The

separation of the two republics was never fully achieved in

practical terms because villages had very active economies

involving Spaniards and mestizos, and also because many

natives lived in cities.

African Grass

With the introduction of cattle raising in the Bogotá

Savanna, the landscape was modified to fit the interests of

cattle farmers. The grasslands depicted in the painting,

therefore, are likely not of the same kind that cover the

savanna today. In the eighteenth century, ranchers

encouraged importing African grasses that provided better

yield for cattle raising. The introduction of African

grasses in the New World, nevertheless, can be traced back

to an earlier date, when they were used in making the beds

in ships for the slave trade.

Land Dispossession

On the painting we can see a dramatic reduction in the area

occupied by native farmlands, in comparison to the vast

pasture lands of the hacienda of Spaniard Francisco

Maldonado y Mendoza. In this sense, this document is

essentially a map of land dispossession, and of the

transformation of the agricultural landscapes of native

societies.

Ridge System

Before the arrival of the Spanish and the introduction of

their methods of farming and breeding, the Muisca that

inhabited the region organized and made use of water sources

through the ridge system. This system consisted of raised

platforms that served as terraces for growing food. They

were traversed by levees that brought many benefits, such as

draining excess water so that the terraces could be sowed

and serving as fishing channels.

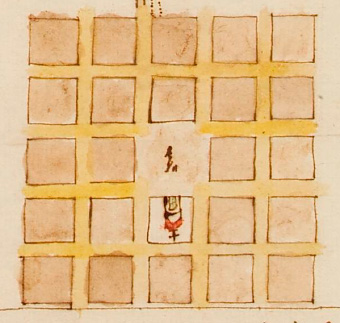

Villages for the Indians

The villages depicted on the map, such as Fontibón or La

Serrezuela, were built as part of a project with which the

Spanish Empire sought to compel natives to live Catholic

lives and to “forget their former rites and ceremonies”. As

a result, natives were forced to abandon their homes and

resettle in villages organized around a main square and a

church, and drawn as a grid. This process was known as the

“reduction” of the natives.

the scale of the map

Unlike modern maps, which ensure accuracy by maintaining a

constant scale throughout the image, the Painting uses a

multiple, flexible and variable scale. The center of the map

—which represents the territory in dispute between Maldonado

and the crown attorney— uses a more precise scale, while the

edges are much more variable, allowing the observer to see

relatively remote landmarks, like the city of Santafé and

the towns of Fontibón and Madrid.

the colors of the map

Although we do not know the origin of the paints used on the

map, the production of inks and colors was a complex craft

involving vegetable and animal pigments that were then

transformed into paint through processes with rich cultural

significance. We have evidence that the Muisca and other

native groups used a wide palette of blue, red and brown

pigments they applied to designs on textiles, rocks and

other surfaces. For this reason, it is possible that some of

the colors used on the Painting were native paints.

Cattle in the Americas

Throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Spain developed a

cattle culture around the raising of cows, sheep, goats and

pigs which depended on the use of horses and dogs to control

livestock that was allowed to roam freely. After being

introduced into the New World, these species quickly

flourished, easily adapting to an environment lacking in

natural predators. Meanwhile, other less wanted species such

as the Norway rat, which had come on the ships of the

settlers, also multiplied.

Francisco maldonado y mendoza

Maldonado y Mendoza was born in Spain in 1551 and moved to

Santafé de Bogotá in 1583. In 1586 he married Jerónima de

Orrego, daughter and sole heiress of conquistador Alonso de

Olalla. That year, Maldonado y Mendoza began buying estates

in the Bogotá Savanna and receiving lands awarded by the

Spanish Crown. By the mid-1590s, Maldonado y Mendoza was not

only the encomendero of the indigenous community of Bogotá,

but owned one of the most prosperous cattle haciendas of the

New Kingdom of Granada. On the painting, we find evidence of

this in the depictions and labels of some of the spaces of

the hacienda: Mill of Don Francisco, steer yard of Don

Francisco, estate of Don Francisco, and so on. His heirs

held on to his power and wealth for over two centuries.

City of Santafé

This map/painting depicts the Bogotá Savanna, a high plateau

on the Eastern Range of the Andes in present-day Colombia.

In the early sixteenth century, the Savanna was occupied by

Muisca indigenous people, of the Chibcha linguistic family.

A Spanish expedition led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada came

to this place in 1536. The city of Bogotá would then become

the center of operations of the Spanish Empire in the area,

and in 1549 it was declared as the seat of the Audiencia of

Santafé.

Old Palisade of the Cacique

When the Spanish arrived, the Muisca were organized in

farming societies with many levels of political hierarchy,

and its leaders lived in ceremonial places surrounded by

logs of wood and decorated with paintings on cotton fabric

of different colors and styles.

Road as Ridge

The map labels the road as a “ridge”. This particularity

reminds us of the fact that many native and colonial roads

in the Savanna were built as raised platforms so that they

would remain dry in rainy seasons. To this day people call

many tracks and roads in the Savanna “ridges”.

Pigsty of the Cacique

Native societies in the New World had domesticated many

animals, among which dogs, turkeys and ducks. In the

Peruvian and Bolivian Andes, they also raised camelids such

as lamas and alpacas, used as pack animals and for their

wool. The inclusion in the map of the pigsty and the grazing

land of the cacique proves that natives also integrated

European animals into their economic activity. This was the

case with chickens and sheep, the latter used for their wool

in order to replace cotton and produce blankets at a lower

cost.

Claims of the Natives

“[…] we come before you to state the troubles and

destructions we have suffered in our town in the form of

damages to our crops. There is a neighbor named Agustín Vela

with over two hundred mules and horses, bovine cattle and

donkeys in our reservation. Before we can harvest our misery

which is wheat, maize, barley and truffles, he brings in his

tame and wild mules and destroys [our crops] having many

lands […] maliciously fattening his mules with our grain

[…]” Natives of Turmequé, 1672.

Construction of Villages

“The buildings of the village should be built in such a way

that the square is placed in the middle in reasonable

proportion, and from it, all streets should branch out with

their building lots according in number to the amount of

inhabitants, and the building lots and houses will be of a

size, with their yards […], so that first and foremost the

villagers can join in building their Church on one side of

the square, the altar facing east and of a grandeur and size

proportional to the village and somewhat larger, and on the

other side build the house of the cacique and lord with

reasonable grandeur, and on the other side the house of

their cabildo and the jail, and on the other, the houses of

the nobles, and behind them, along the roads, the rest of

the building lots […]” Tomás López Medel, 1559

Natives in the City

“Having understood the disorders and excesses seen in this

city of Santafé de Bogotá due to male and female Indians,

mestizos, and mulattoes that are without a master to serve

and for this reason are found idle and like vagabonds, which

often results in grave damages and problems […] and wanting

to provide aid to this as you see fit so as to put an end to

such disorders […] I name him administrator of the said

Indians and mulattoes […]” Instructions for the

Administrator of Indians of Santa Fe, 1594.

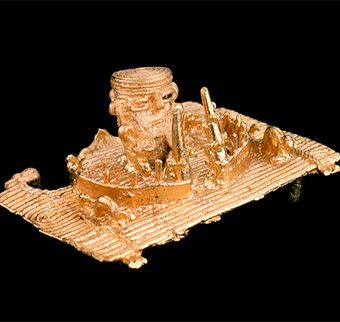

Francisco Maldonado de Mendoza

Votive figure in goldsmithing (Muisca)

Aerial photo of a ridge (1956)

Village of Suta

Village of Guasca

Click on the icons on the map to reveal some of its

characteristics.

Browse the map and zoom in and out to see more details.

This is the Painting of the Land of Bogotá laid over a

present-day map of the area. The overlay is approximate, given that

the scales of the painting and the present-day map do not fully

coincide.

This is a skewed version of the

Painting of the Lands of Bogotá we put together to show the

difference between the scale it used and the scale we use today.

This is how the Painting would look if we made its scale to

coincide with the scale of our present-day map.