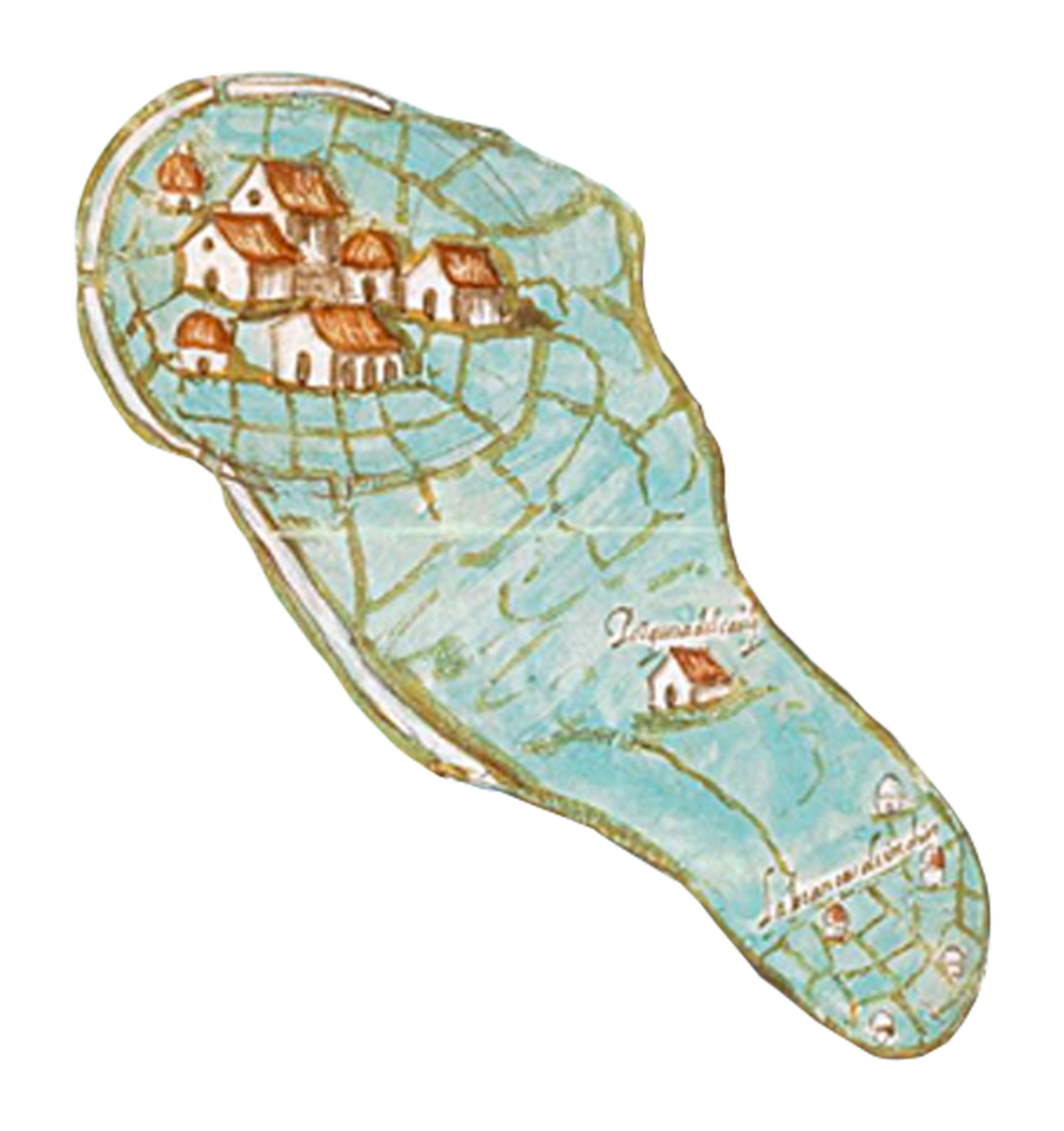

The Painting of the lands, marshes, and swamps of the town of Bogotá was presented as evidence during a 1614 legal proceeding brought by the crown prosecutor of the New Kingdom of Granada against Francisco Maldonado y Mendoza, a renowned encomendero, over the ownership of lands in the Bogotá savanna.

The map features the Bogotá savanna, a high plateau on the eastern mountain range of the northern Andes in modern-day Colombia. In the early sixteenth century, the savanna was occupied by the Indigenous Muisca people of the Chibcha linguistic family. A Spanish expedition led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada arrived there in 1536. From that moment on, the city of Bogotá became the base of operations for the Spanish empire in the region and was designated as the seat of the audiencia of Santafé in 1549.

The Painting of the lands, marshes, and swamps of the town of Bogotá is a manuscript that works both as a map and as a landscape painting and belongs to the genre of legal maps.

The estate (hacienda) depicted on the painting belonged to Francisco de Maldonado y Mendoza. His descendants obtained titles of nobility and the estate became the center of the Marquisate of San Jorge.

Europeans coined the term “indios” to group the different societies of the New World into a single category. This practice originated during Christopher Columbus’s first travels. The label imposed many negative stereotypes on Indigenous populations.

The towns that today populate the savanna were not always there, but were the result of a project set in motion by the Spanish empire aimed at making “indios” live Catholic lives (what they referred to as “life in good order”).

The first instructions for the building of villages were decreed by colonial officer Tomás López Medel in 1559 and they caused many serious problems within Indigenous societies. Reducciones not only created conditions favorable to epidemics due to overcrowding, but also generated conflicts between Indigenous authorities and communities.

On the map we can see where the “old palisade of the cacique” used to be. In the sixteenth century, the Muisca of the Savanna had ceremonial centers that were known as “palisades.” These played an important role in their political organization.

The creation of towns was part of a set of measures aimed at creating two separate “republics” with different legal responsibilities: one of indios living in towns and another of Spaniards living in cities. This is why the “town of Bogotá” and the city of “Santa Fe” appear as different places on the map: the town of Bogotá where Funza sits today, and the city in the place of contemporary Santafé de Bogotá.

Although the landscape in the map is dominated by animals such as cows, sheep, pigs and horses, none of these animals were native to Andean landscapes.

In the savanna’s water-rich ecosystem, the Indigenous Muisca people designed a system of cultivation terraces made up of raised beds and elevated platforms. The terraces, in turn, were traversed by ditches that drained the excess water and served as fishing canals.

The introduction of cattle raising following the Spanish invasion changed the landscape of the savanna forever. The raised-bed and canal systems were not practical from the perspective of ranching. For this purpose, it was more useful to level the terraced fields and convert the landscape to .

Resguardos were communal lands that Indigenous people could farm. They came about as part of the legal reform of 1593, known as the land compositions (composiciones de tierras). Until then, most lands had remained in the hands of Indigenous people.

In 1593—the same year as the reform—the then Audiencia president Antonio González created an administrative mechanism for a Spaniard to distribute Indigenous labor. This new official was authorized to tell Indigenous people where to work and to regulate how they managed their affairs.

Resguardos were created at a time when the imperial administration defined Spaniards and Indigenous peoples as having different economic capacities: Spaniards had extensive commercial lands while Indigenous people had restricted economies supervised by the imperial administration. Indigenous people lost access to about 95% of the lands that had been available to them for farming before the conquest.

In this sense, this is a profoundly violent map. It is a map of land dispossession and of the transformation of the Indigenous agricultural landscapes into grazing pastures for Spanish estate owners—estates on which Indigenous people were forced to work. A few details on the map reveal the marks left by this process, such as the place that indicates the location of the former cacicazgo, or the small area allotted to the community’s resguardo, in contrast with the large estates owned by Spaniards.

Villages and resguardos have had a long and unstable trajectory since the sixteenth century, going through waves of confrontation and resurgence. Most municipalities on the high plateau were former Indigenous villages. In the case of resguardos, after many attempts to dismantle them during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Political Constitution of 1991 made it possible for them to become ethnic territories once again and since then resguardos have offered Indigenous peoples with new possibilities of ethnic autonomy.